The Paris Agreement calls for bold action to mitigate climate change. This cannot be achieved by renewable energy and energy efficiency alone and requires for a major shift in the way we produce, use and recover materials and products.

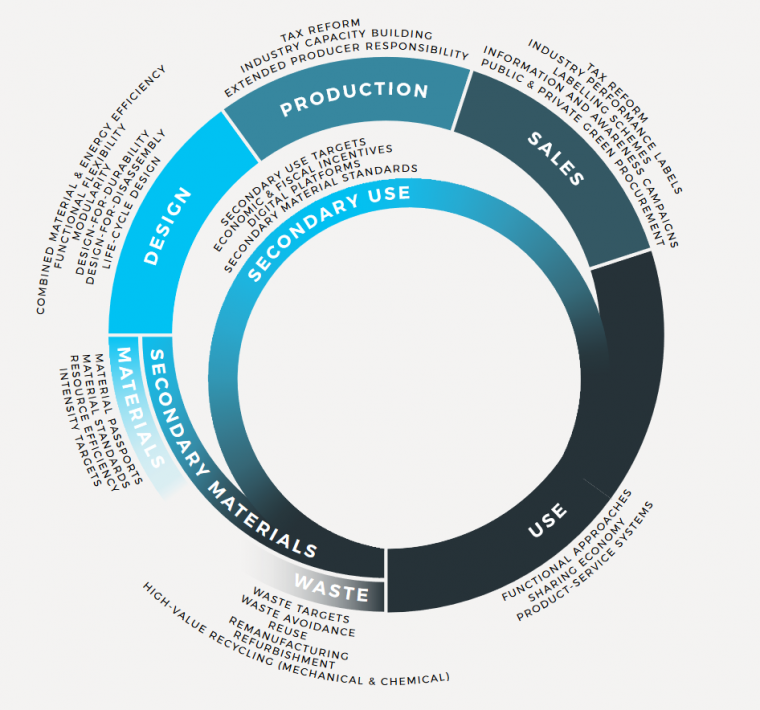

A fundamental shift is needed in the way we deliver on societal needs and mitigate emissions. The circular economy is “restorative and regenerative by design, and aiming to keep products, components, and materials at their highest utility and value at all times”. It is a far-reaching concept aiming to optimise the way our economies deliver upon societal needs, and can play a crucial role in realising the transformational change needed to meet European climate targets.

Policymakers should act now to catalyse the transition to a low-carbon circular economy

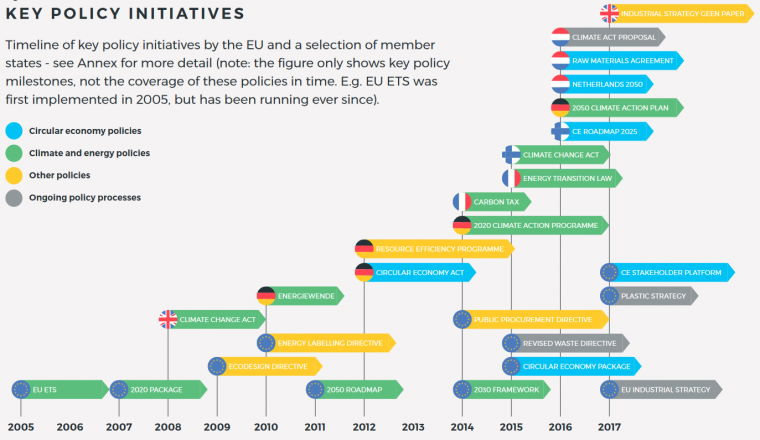

Implementing the circular economy at scale requires the commitment from European policy makers and front-running member states. Important first steps are being taken, for example by Finland, France, Germany, The Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Housing and mobility value chains are central to the European economy and powerful engines for change. They are also major users of key materials such as plastics, cement, steel and aluminium, whose value chains are responsible for 70 percent of the European Union’s (EU) emissions.

This study, combines a European perspective with a focus on the above mentioned value chains, material streams and jurisdictions. It forms part of a broader project led the European Climate Foundation’s Industrial Innovation for Competitiveness (i24c) initiative, which also involves quantifying the emissions reduction potential of circular economy strategies in the EU.

This paper intends to contribute to the debate on effective policy levers for a low-carbon circular economy. It explores how to create a tipping point whereby the transition is not just necessary, but also inevitable.

Systemic inertia and market distortions must be addressed

The transition to a low-carbon circular economy is an ambitious task that requires systemic intervention. This requires an EU vision to avoid that diverging socio-economic interests of member states will lead to watered-down, consensus-driven policies to ensure political backing from incumbent industries. For example, ambitious waste policies going beyond incremental improvement and adhering to circular economy principles are scarcely pursued as they would require leapfrogging by many member states.

The transition to a low-carbon circular economy also faces systemic inertia. As long as companies operate in a tax regime which encourages material overconsumption, which keeps labour costs high, maintains tax exemptions for concrete and subsidies for fossil fuels, circular business models fight an uphill battle against linear incumbents, despite the subsidies for circular design, business models and innovation.

Circular transformation also creates winners and losers, as evidenced by the current transition from a fossil-fuel to a renewable energy system. This requires policymakers to act carefully in front of vested interests that will resist change unless they see a role for themselves in the future. For example, Europe has built considerable incinerator capacity, valorised by the focus on waste incineration promoted by the renewable energy Directive, while the circular economy calls for a widely more ambitious approach.

Low-carbon and circular policy are complementary and must join forces

To decisively engage in the transition, it is essential that climate and circular policy join forces. For example, material-use strategies are central tenets of the circular economy and promise to deliver the transformational change needed to decarbonise our economies in line with the Paris Agreement, yet they are scarcely pursued. With an estimated 67% of global greenhouse gas emissions stemming from material management, sustainable sourcing, cycling and the efficient use of materials should be just as high on the agenda of climate policymakers as renewable energy and energy efficiency.

However, our understanding of the mitigation potential of circular economy strategies lags behind on our understanding of the impact of energy-related measures. Similarly, there is more information on fuel related emission footprints than on material-related footprints. Efforts are needed to quantify the mitigation potential of circular economy strategies, such as the work currently being conducted by i24c. Additionally, efforts for comprehensive target setting, for example adding material efficiency to energy efficiency targets, could be an effective pathway to link climate and circular economy policy.

Furthermore, an expansion of current jurisdiction-based carbon accounting toward consumption-based systems would help reveal circular mitigation opportunities from improved material flows, cross-sector and cross-border initiatives. As illustrated by the increase in European lifecycle emissions, significant emissions mitigation can be reached by addressing global consumption patterns and associated material flows.

Low-carbon circular policy must be carried by a wide range of institutions and policymakers

The breadth of the circular economy requires that a wide range of institutions and policymakers be engaged in the transition. This includes both geographical jurisdictions – European, national, local – and thematic institutions – social, economic, environmental.

The EU has a major role to play to support ambitious research and innovation programmes, to harmonise complex, pan-European value chains and to enable economies of scale in the way industry delivers value to society. European policy engagement should include continued efforts to lay out a comprehensive and integrated policy framework through Directives and, when possible, regulation. In the short-term, Ecodesign and EPR appear to be highly interesting pathways to pursue, able not only to affect design and manufacturing, but also to trigger positive impacts down the value chain, and in particular on waste management.

Member states are pivotal in contextually translating European directives, and have also demonstrated their ability to enrich the policy field with more ambitious, targeted and innovative policies. They have more room to manoeuvre with economic and fiscal measures to drive front-runner programmes, accelerate innovation and prepare the regulatory field. Making circular economy and climate action the central topic of the EU structural and cohesion funds, can help avoid that the progress gap between member states widens further.

A real transition to a circular economy, without shifting environmental impacts abroad, requires at least understanding the full life cycle of products, and strengthen international cooperation where parts of the life-cycle are outside the EU. For climate action, the Paris Agreement provides a unique opportunity to improve the transparency of the carbon impact of consumption habits as well as the our understanding of emissions along product life cycles. It also provides an opportunity to strengthen international cooperation along value chains, in particularly of carbon-intensive products and materials.

The circular economy is a major opportunity for economic competitiveness and able to contribute as much as 1.8 trillion euros to the European economy by 2030. The success of a transition to a low-carbon circular economy therefore requires careful integration within the European ‘Jobs, Growth and Competitiveness’ agenda. While, the circular economy traditionally lands with environmental institutions, their reach is limited without engaging economic and social institutions, and even tax authorities. The example of the Netherlands, where circular economy policy is led from the top of the cabinet, demonstrates the advantages of positioning the circular economy at the core of socio-economic development, rather than marginalising it as an environmental issue.

Client: Circle Economy/European Climate Foundation with funding from SITRA

Partners: Allen & Overy, Material Economics

2017